While interest rates are slowly rising, they remain at historically low levels. As a result, many income-focused investors continue to search for the best high dividend stocks to meet their long-term investing needs.

High dividend stocks can be an appealing way to fund a portion of retirement through dividends rather than the selling of shares, but high-yields can sometimes be a warning that a company’s business model is broken and best avoided.

In other words, some beaten-down, high-yield stocks are value traps with poor dividend security, making them unacceptable for a retirement portfolio.

Let’s take a look at Tupperware (TUP), whose 4.6% dividend yield and track record of paying uninterrupted dividends for more than 20 consecutive years may at first make it seem like an appealing choice for high-yield investors (it’s a famous household brand after all), to see if this company’s dividend is suitable for low-risk income investors.

Business Overview

Tupperware Corporation was founded by Earl Tupper in 1946 in Orlando, Florida, and incorporated in 1996. In 2005, after a series of large-scale acquisitions of different product segments, the company changed its name to Tupperware Brands.

Today, Tupperware is a global direct-to-consumer marketer of numerous household goods, including containers, cookware, knives, microwave products, microfiber textiles, water-filtration related items, and an array of on-the-go consumer products.

The company’s business model is heavily reliant on social marketing, also called multi-level marketing, in which customers become Tupperware consultants (3.2 million at the end of Q3 2017) who market to friends and family via its famous group demonstrations (such as the famous “Tupperware parties”).

The company has also diversified into skin and hair care products, cosmetics, bath and body care, toiletries, fragrances, jewelry, and nutritional products via its acquisitions of numerous brands: Avroy Shlain, NaturCare, Nutrimetics, Fuller, BeautiControl, Armand Dupree, Fuller Cosmetics, Del Baul de la Abuela, Natural Forte, Fuller Royal Jelly, Nutri-Rich, NC Express, and Nuvo.

Tupperware is a geographically diverse company. For example, in 2016 approximately 91% and 100% of Tupperware’s sales and net profits, respectively, were from outside the U.S., with 66% of sales coming from fast-growing emerging markets such as Mexico, Brazil, India, and China.

Business Analysis

It’s been a rough few years for Tupperware, with the company facing declining sales, earnings, and cash flow since 2013.

The company announced a major restructuring in July 2017, shutting down its North American Beauticontrol business, which has been suffering from declining sales and profitability.

This will mean that going forward, even less of the company’s sales will come from North America, and management expects to see cash costs of $90 to $100 million associated with the restructuring through the end of 2019 ($25 million in 2017).

The restructuring is also designed to consolidate the supply chain, in order to decrease annual marketing expenses by $35 million per year.

However, this restructuring means that, while growing overseas sales have halted the top line decline, earnings and free cash flow are likely to remain depressed over the next few years.

This will likely mean a decline in the company’s margins and returns on capital, which on the plus side have historically been above the industry average (Tupperware sells premium, high margin products).

The big concern for dividend investors is that declining free cash flow, which is what funds the dividend, could put the current generous payout at risk, especially given the company’s plans to aggressively de-leverage its balance sheet (pay down debt).

Now the good news is that management has a multi-pronged long-term international growth strategy it calls “Vision 2020”.

The strategy calls for more aggressive international expansion (sales force is up 4% this year), but also:

- Increased consultant support, including greater training and company sponsored weekly events

- Move from brochure-based sales to more one-on-one demonstrations (except kitchen products)

- Kitchen products demonstrations moving from one-on-one to group presentations

- Creation of “experience centers” where consultants can do more interactive hands-on demonstrations

- Greater use of social media and a bigger push for business to business sales (such as selling to restaurants)

- Reaching out to former sellers in an effort to make them “brand ambassadors”

In addition, the company plans to launch over 100 new products in the coming years, which it can use to more fully stock its upcoming brick and mortar stores.

However, there are numerous problems with Tupperware’s long-term strategy, including a potentially fatal flaw in its core business model.

Key Risks

First, because 91% of sales (and 100% of profits) come from outside the U.S., Tupperware has large foreign currency exposure.

This means that when the US dollar rises against other currencies (such as when U.S. interest rates rise relative to rates in other countries, as is happening now), local sales end up translating into fewer dollars, and thus create profit and dividend growth headwinds.

A stronger dollar also makes Tupperware’s products more expensive (and less competitive) overseas, which is literally where more than 100% of growth is expected to come from in the future.

That’s because mature markets, such as the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Australia are seeing declining sales and earnings over time, even in newer and more trendy business segments such as cosmetics and health supplements (which is why Beauticontrol was shut down).

But what about fast-growing emerging markets? These have much larger populations, rapidly expanding economies, and booming middles classes. Could not these, when combined with 100 new products in development and a more hands-on (traditional retail) focus help Tupperware grow strongly as it has in the past?

While this is certainly possible, there are two main risks to the company’s turnaround plan.

The first is that while Tupperware sells branded products, those operate in highly competitive industries, such as cosmetics (one of the highest margin businesses in the world) and nutritional supplements.

The problem is that major competitors with far larger economies of scale (i.e. lower production costs), huge marketing budgets, and greater distribution channels (shelf space monopolies) offer competing products in more mainstream (and often more successful) ways, such as through grocery stores, big box chains (like Wal-Mart), specialty stores, and online.

In other words, Tupperware’s approach, which is also known as multi-level marketing (MLM), is a very limited business model, which the company’s plans for brick-and-mortar stores is an admission of.

Also keep in mind that not only are physical stores expensive to open and maintain (much higher fixed costs in the company’s future), but the entire brick-and-mortar retail industry is undergoing massive upheaval right now due to the rise of e-commerce.

In fact, between January 1, 2017, and October 25, 2017, more than 6,700 U.S. retail stores closed (on pace for 8,600 this year), which is far worse than the 6,163 store closings in 2008 during the worst financial crisis and recession since the Great Depression.

Or to put it another way, physical retail is currently undergoing massive disruptive changes in which even the most successful retailers are struggling to maintain sales and market share. Thus Tupperware’s plans to incorporate brick-and-mortar into its existing MLM business model could very well prove to be a mistake.

Perhaps the biggest threat to Tupperware is that even if it can achieve strong growth in emerging markets, which is hardly a given (Malaysian, Indonesian, and Indian sales dropped by 2%, 17%, and 32% in Q3 2017, respectively), that might not make Tupperware a sustainable company.

That’s because the MLM business model has is basically a hybrid franchise model, pioneered by companies such as Amway, Tupperware, Herbalife, Avon, Mary Kay and The Pampered Chef.

The business model calls for sellers to recruit customers themselves to sell the products, with the recruiting associate then getting a percentage of any sales these recruits generate.

For example, a Tupperware consultant may recruit five people to also sell Tupperware-branded products, and each of those try to recruit five people, who then recruit five more each, resulting in a total of 125 consultants selling the product.

The first person in the chain then benefits from a large and growing stream of recurring revenue (generally consultants have to sell a minimum amount of merchandise each month or quarter or buy it themselves).

The company benefits because each consultant in the distribution network represents guaranteed sales, for as long as they remain a part of the program.

Of course this sounds awfully close to a pyramid scheme (which are illegal in all 50 states as well as violate federal trade laws), which many MLM companies have been accused of. In fact, in 1979 the Federal Trade Commission investigated Amway to determine whether or not its MLM business model violated federal laws.

The FTC determined that MLM companies are not necessarily illegal pyramid schemes as long as the focus remains on actually selling reputable products, rather than merely recruiting new sellers.

Specifically, the FTC established three key provisions for determining the difference between a legitimate MLM model and a pyramid scheme, which today are knowns as the Amway rules:

- The 70% Rule: Requires that a distributor sell 70% of his or her purchased inventory to customers each month.

- The Ten Customer Rule: Requires distributors to make at least one retail sale to each of 10 different customers each month.

- Inventory Buy Back Program: Requires the company to buy back any unused and marketable products a distributor can’t sell.

However, the stigma of MLM remains, which is why such companies have rebranded themselves as network marketing companies, affiliate marketing organizations, or social networking firms (which is how Tupperware refers to itself).

Fortunately for Tupperware, the FTC, which has launched investigations against 26 MLM companies since 1975, has never accused Tupperware of violating the Amway rules.

In other words, Tupperware’s business model is, at least legally speaking, legitimate. However, that doesn’t mean that it’s one that can sustainably grow in the long-term or support safe and steadily growing dividends.

Here’s how it works. A new Tupperware consultant pays $99 for a starter kit.

You can either pay upfront, or $30 for a first installment, with the remaining $69 waived if you sell $900 of product within the first 60 days.

Consultants are paid entirely on commission, receiving 25% of sales, which rises to as much as 35% if they hit certain monthly sales volumes.

- Base compensation: 25% of sales

- $1,500-$9,999 per month in sales: 30% of sales

- $10,000+ per month: 35% of sales

- Minimum sales per 4-month period (including your own purchases): $250

Because Tupperware doesn’t directly pay consultants or require them to recruit new sellers, it is within current U.S. trade laws.

However, in order to become a top seller (achieving 35% sales commissions, including in your recruited network) and qualify for perks such as “exotic trips, use of a new cars, diamonds, and cash bonuses,” consultants will need to establish a rather large network of sellers beneath them. Consultants only receive credit for sales of sellers three levels beneath them.

The company has 12 ranks of sellers beginning with consultants, and depending on how many recruits and sales you obtain, sellers can rise to the level of “Presidential Director.” Each rank offers a greater percentage of total network sales, plus the above mentioned perks.

In order to become a manager (first promotion), you need to:

- Be selling $500 of product every 4 months

- Recruit a minimum of three sellers into your first level

- Your sellers need to be grossing at least $2,500 every 4 months

Becoming a manager means you are eligible for two bonuses.

The first is the Profit Plus Bonus: 2% of commissionable volume (75% of gross sales) that your team sells. As you recruit more people and hit higher sales volumes you get promoted to higher ranks of managers, resulting in even higher bonuses.

The second bonus is the Vanguard Bonus, which is a monthly bonus based on monthly commissionable volume.

The next rank category is directorship, which removes the cap on receiving commissions on just the top 3 levels of sellers you’ve recruited and also results in team bonuses, of up to 8% of commissionable sales (on top of the personal sales commissions of 35%)

Further promotion to Star Director (which involves several company building milestones), means that you now get a cut of the sales created by your director teams.

You get the idea – while you don’t necessarily HAVE to recruit new sellers (which would make it a pyramid scheme), and the company doesn’t pay bonuses specifically for each new recruited seller (which would violate the Amway rules), Tupperware sales reps have a large incentive to recruit as many people as possible, as well as ensure that everyone sells as much as possible.

In theory, there is nothing wrong with this business model. After all it, it opens up the chance for entrepreneurial greatness for anyone, regardless of wealth (you can start for as little as $30), gender (most Tupperware sellers are women), or education level. And if you manage to build a team that can sell $26,667 a month of product, than you can personally make $7,100 yourself.

However, the problem with Tupperware’s business model (and all MLM businesses) is that over the long-term, while it generates strong and usually recurring sales for the parent company, it actually makes very few individual sellers as rich as these exciting recruitment brochures indicate.

Keep in mind that $260 in Tupperware commissions is just an average, one that is skewed higher by those few sellers that are very high up in the company and making good money. In reality, in mature markets (such as North America), almost no sellers end up making anywhere near the median U.S. income ($59,039 in 2016).

For example, according to Tupperware’s own disclosures, just 1 in 1,667 Canadian sellers earned $50,000 ($39,080 US) or more in 2016.

Why is that? Because the MLM approach to selling products, while good in theory, has massive flaws. These include high costs (a medium Tupperware container generally runs $17 compared to a $3 rival product in K-mart), and less visible exposure.

That basically means that most consumers will buy the product categories marketed by Tupperware Brands in either grocery stores, big box retailers, or increasingly online.

That’s because, while Tupperware products may be higher quality, most consumers value lower prices and greater convenience, which is why the MLM business model has never grown to dominate retail.

In fact, in 2015 total global MLM sales were $183.7 billion (20% in the U.S.) and generated $73.4 billion in commissions to sellers. Tupperware’s $2.3 billion in global sales means it had a 1.25% market share of the MLM market that year.

However, in 2015 total global retail sales were $23.93 trillion, meaning that MLM businesses finished the year with a market share of just 0.77%. This is because MLM is merely a niche market, one that hasn’t been able to compete with the better prices or greater convenience of traditional brick-and-mortar retail.

And now that e-commerce is making it possible for consumers to access a much wider variety of quality products, at even lower prices, with even greater convenience (Amazon is offering 1 hour shipping in some cities), the MLM industry is likely to have an even greater challenge in achieving or sustaining growth.

In fact, the only reason that Tupperware is growing at all is because it’s targeting emerging markets, where the MLM business model is relatively new and most people don’t realize that it, by definition, can’t be a path to riches.

After all, every new seller you recruit also becomes a competitor, and because the products marketed by MLM companies can’t compete on price or convenience with traditional retail, much less online retail, the ultimate size of the market is capped at just a fraction of the overall global retail pie.

Which explains why Tupperware’s U.S. business generated zero profit in 2016, despite being 71 years old. As markets become mature and saturated with MLM sellers, seller turnover increases (as sellers realize they can’t make any money and quit) and costs of acquiring new sales associates rises to match the total lifetime value of the sales the associate can generate.

Even if Tupperware blows up in emerging markets, it’s likely just a matter of time before the same realities of MLM (no one but the company makes money) become apparent, and sales, earnings, and free cash flow growth in those markets also dry up.

As a result, Tupperware’s turnaround plan likely won’t make it a good dividend stock over the long-term. Even with 100 new product launches and increased marketing to obtain sales associates in emerging markets, the MLM business model is one that just doesn’t seem able to compete in the modern world with giant rivals such as Wal-Mart (WMT), Costco (COST), and Amazon (AMZN).

This is why it’s ironic that Tupperware wants to now invest massive amounts of capital into its own retail store fronts. The company is basically admitting that it’s core MLM model has peaked and now is hoping that brick-and-mortar, an industry being severely squeezed (some would say decimated) by e-commerce will prove to be its salvation.

The bottom line is that, while Tupperware may make good products and isn’t technically a pyramid scheme, its MLM business model is fundamentally uncompetitive in today’s retail world.

The company’s current turnaround efforts are also going to cost a lot of money, squeezing its margins and free cash flow even further over the short-term. This is likely to make its dividend increasingly dangerous over the coming years and potentially even unsustainable.

Tupperware’s Dividend Safety

We analyze 25+ years of dividend data and 10+ years of fundamental data to understand the safety and growth prospects of a dividend.

Our Dividend Safety Score answers the question, “Is the current dividend payment safe?” We look at some of the most important financial factors such as current and historical EPS and FCF payout ratios, debt levels, free cash flow generation, industry cyclicality, ROIC trends, and more.

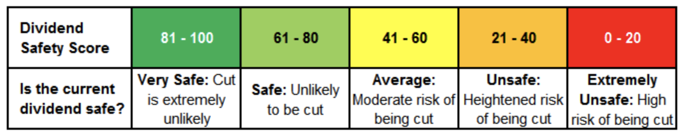

Dividend Safety Scores range from 0 to 100, and conservative dividend investors should stick with firms that score at least 60. Since tracking the data, companies cutting their dividends had an average Dividend Safety Score below 20 at the time of their dividend reduction announcements.

We wrote a detailed analysis reviewing how Dividend Safety Scores are calculated, what their real-time track record has been, and how to use them for your portfolio here.

Tupperware has a Dividend Safety Score of 30, indicating a potentially unsafe payout that could be at greater risk of being cut in the future. This shouldn’t be a surprise to investors, given that the company has seen shrinking sales over the past few years, which has forced management to freeze the dividend since 2014.

What’s worse is that Tupperware’s earnings and free cash flow have been declining over this time, meaning that even with a flat dividend, the EPS and FCF payout ratios have been steadily climbing.

In fact, the high cash cost of the restructuring that Tupperware has just begun has resulted in its FCF payout ratio over the past 12 months rising to 72%.

For the full year, management expects free cash flow to range between $165 million and $175 million, compared to dividend payments of approximately $140 million. That would put the FCF payout ratio around 80%.

To be fair, Tupperware’s free cash flow is being reduced by $25 million this year as part of its $90 million to $100 million three-year restructuring plan. Although that is a real cash cost, it shouldn’t be repeated once the turnaround expenses are complete.

If we ignored the cost this year to get a better sense of Tupperware’s “normalized” free cash flow, the company’s full-year payout ratio sits closer to 72% – still on the high side for a company with future growth uncertainties.

Given that the company’s FCF has actually shrunk since 2009 (the depths of the great recession when all retail sales were terrible), this doesn’t bode well for the security of the current dividend if the turnaround plan does not rejuvenate growth over the coming years.

That’s especially true given that Tupperware has seen its debt load increase substantially over the years due to its ongoing acquisitions of new brands and product categories.

As a result, Tupperware has a lot of net debt for its small size and carries above-average leverage compared to its peers.

While Tupperware currently still enjoys an investment grade credit rating, management is aware that the company’s debt is a little high, which is why it plans to deleverage in the coming years.

While management has said the dividend remains the company’s top priority, its declining FCF could make it harder for Tupperware to deleverage while preserving the payout in the future.

Furthermore, if U.S. interest rates continue rising and management is faced with a potential credit downgrade to junk status (which would raise the company’s debt refinancing levels much higher than its already steep 5.9% borrowing costs), shareholders of Tupperware could eventually be faced with a dividend cut.

Tupperware’s dividend looks secure over the short-term, but growth headwinds, an elevated free cash flow payout ratio, and a shifting retail landscape make the company’s payout a lot less certain over the medium to long-term. My personal preference is to avoid these potential value traps sooner rather than later.

Tupperware’s Dividend Growth

Given the troubled nature of Tupperware’s business, especially its declining unadjusted earnings and free cash flow, investors shouldn’t be asking how quickly Tupperware’s dividend can grow, but rather will it even be maintained at current levels over the coming years. You can see that the company has only increased its dividend in about five of the last 20 years.

Management is guiding for 2% to 3% local currency sales growth (not counting potential negative currency effects) in 2017, translating to adjusted EPS (excluding restructuring costs) growth of 8.7% to $4.77 per share. That would represent a full-year adjusted EPS payout ratio of 57%, which is above management’s stated 50% adjusted EPS goal.

Keep in mind that while certain non-cash expenses might not affect free cash flow (such as writing down goodwill from overpaying for acquisitions in the past), Tupperware is predicting $90 to $100 million in cash flow negative restructuring costs.

This is a very important distinction because dividends aren’t paid out of adjusted EPS (GAAP EPS minus non-recurring items), but free cash flow, which continues to deteriorate.

While Tupperware has the ability to temporarily cover any FCF shortfalls (if FCF payout ratio goes over 100%) with cash on the balance sheet, ultimately this would be dangerous and unsustainable to do over the long-term.

Valuation

Over the past year, Tupperware shares have underperformed the S&P 500 by about 20%. As a result, the company’s valuation metrics look relatively attractive at first glance.

For example, TUP’s forward P/E ratio of 11.4 is much lower than the industry median of 17.2, the S&P 500’s 18.2, and the stock’s historical 16.2 multiple.

Similarly, TUP’s dividend yield of 4.6% is higher than the stock’s five-year average yield of 4.1%:

That being said, Tupperware seems like a business that could face real challenges within the next five years. The company has struggled to achieve profitable growth in recent years, and the continued rise of e-commerce around the world could put further pressure on the MLM business model.

For those reasons, TUP’s low multiples and relatively high yield seem more like signs of a value trap than a bargain. The current yield doesn’t compensate investors very well for the risks facing the company.

Conclusion

Tupperware may be a household name, but it faces a very different market environment today compared to the retail world of the 1950’s, when Tupperware was at its peak.

Specifically, the massive disruption in global retail driven by Amazon and Alibaba (the Amazon of Asia) means that Tupperware’s premium products, sold via a potentially flawed MLM model, isn’t likely a long-term sustainable avenue to profitable growth.

Despite Tupperware’s appealing yield and seemingly “cheap” valuation (at first glance), this is still a risky stock that does not seem suitable for low risk income investors, such as retirees looking to live off dividends.

Thank You Brian. I bought Tupperware for the dividend on 12/16/16 based on information I found using a free dividends site but wound up selling it on 8/31/17 because it had run up nicely but then came back down almost to my original purchase price. It took a lot of research from multiple sites to try and piece together why it was correcting and was it temporary or long term. With my subscription to your service, that information is all here in one place and validates I made the right decision. By just avoiding one bad decision a year, the subscription pays for itself.

Nice article! i don’t own any of TUP. I might initiate a small position.

really !!!

Another great analysis. Your website has made me a lot of money with your in-depth, articulate analyses. No other dividend website comes close to the quality of Simply Safe Dividends. It would be very difficult to manage my retirement portfolio without input from your website. I use it constantly.

Ray Nicholus